NOBODY SAID IT WOULD BE EASY (3 JUL 2015)

After a couple of nights’ recovery time in Tvøroyri, it was time once again to move on. Passage planning in the Faroes revolves very much around the diktats of the “Red Scare Book”, or to use its catchier Faroese title, the “Streymkort fyri Føroyar”. Essentially this is a tidal atlas, and once you have worked out exactly what time you are using as a datum (Slack water at Suduroy for chart 0, or the moon’s meridian passage at chart 6, both handily available in the Almanakkin in Faroese), is quite easy to use. It also contains useful nuggets of information such as: “Our old ones had a proverb, saying: ‘Do he, (the general weatherman), know, that the vind will come from that or that direction, so the current there and there will go quite mad'”;

And, furthermore:

“If you put a finger in your mouth, and so up in the air, and the finger being cooled on one side, then the weather is not quite calm. In sailing vessels the captain often used the finger rule.“

It is, however, essential for making passage between the islands without endangering one’s vessel and crew in the quite brutal tidal streams, which can throw up overfalls in the calmest conditions, and damage or overwhelm them in wind-against-tide conditions.

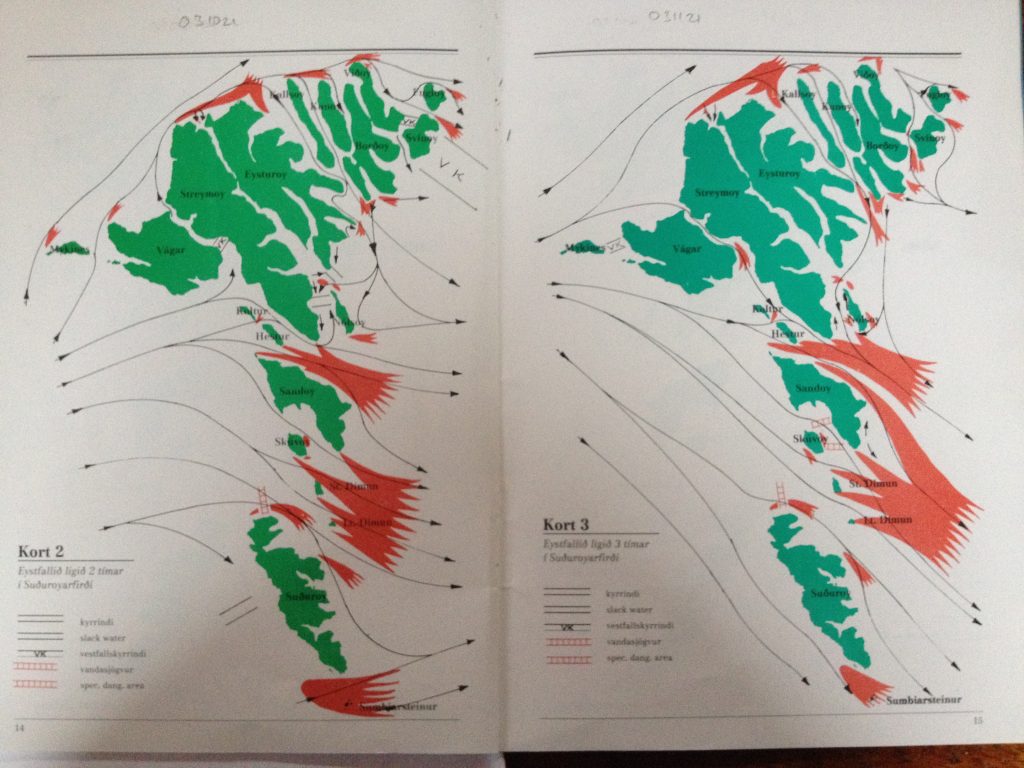

Here is a typical page:

The red areas indicate dangerous overfalls in wind-against-tide conditions, with the black arrows indicating general direction of tidal streams. You may also notice red “ladders”, which are overfalls which are dangerous in any conditions, and no-one in their right minds should attempt to go that way.

Yesterday we chose to sail from Tvøroyri on Suðuroy, the southernmost island, to Sandoy, 20 miles further north. We left shortly after midday to get the favourable tide, and with SW’lies forecast, we should not have too many problems with the red “hands”. Unfortunately, though the tidal predictions are pretty much spot-on, the winds are more difficult to forecast accurately, because someone put a whole bunch of islands in the way. As you might have guessed by now, the wind was north of west, making the red hands potentially dangerous, so instead of having a pleasant and fast sail, we had to dodge between islands avoiding the red bits, at times making barely 2 knots despite log speeds in excess of 6, and being tossed about like the proverbial cork (kids, a cork is what used to be used to stopper bottles of Mummy and Daddy’s special Ribena, before someone decided to take the fun out of it. They are very buoyant but are not stable. Corks, that is, not Mummy and Daddy). We eventually got uptide of Stora Dimun and could relax for a while, even managing to sail for a bit, before turning north to Sandur harbour, using a channel which an hour beforehand had been unusable. Just to make life interesting, the visibility by now had clamped right down and we went into blind navigation mode, with Stu exercising his newly-acquired skills at the chart table, and me on the helm. The breakwater of the harbour appeared out of the greyness, and we soon felt our way in to what turned out to be quite a cute little harbour. We were alongside at around 1900, and having secured and had the compulsory conversations with curious locals, we tucked into our dinner before having a walk through the small but pleasant village, whose main attraction is the church, traditionally built of wood with a turf roof.

We had a slightly lazier morning this morning, but before leaving I had to change the engine oil, after his first 50 hours’ running. This was not too trying, and the harbour even had a waste oil tank. Once the job was complete, we slipped shortly after midday, heading for Miðvágur, on the island of Vagar, to the NNW of Sandoy. The trip started off with a favourable breeze, so once clear of the bay, we set all sail and pottered at a leisurely 4 knots with just a little tide against us for the first hour. Unfortunately, just as we got her going nicely, the wind died, and we had to start the engine again, motoring the rest of the way in almost flat calm (actually flat calm at times). We crossed an area of red during the afternoon, which in places, even in calm conditions, had white water and standing waves. It was easy to see how dangerous these areas could be in less favourable conditions.

We arrived in Miðvágur at around 1700, and after some discussion with random locals on the fishing boat quay, selected a berth alongside an old, but well looked-after, retired fishing boat. Here we intend to stay for a day, to see the lake nearby which empties straight over a cliff into the sea, and also the local Second World War museum.